Source: Andrzej Zembik & Jacek Swaton, Czestochowa,

Na Starej Fotografii, 1994

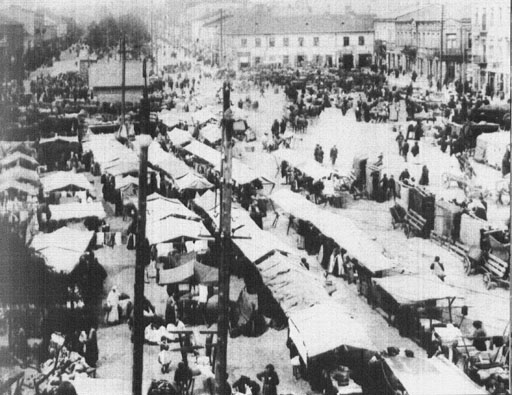

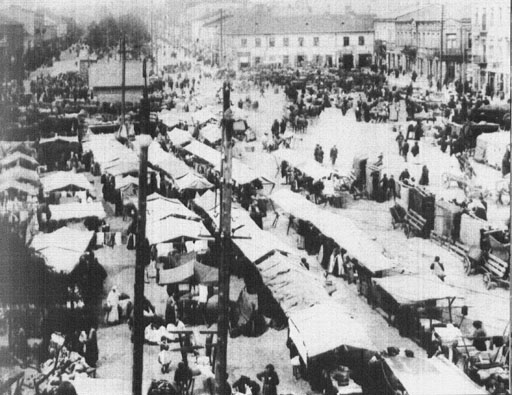

Czestochowa Marketplace at the Turn of the Century - 50 Yards

from the Family Home

by Barry Hantman

Copyright Hantman 1997

My grandmother, Sylvia Zuckerman, died this past year. She never spoke to me about the old country. I know nothing about her childhood, virtually nothing about where she lived, and very little about her parents. Iím sure she spoke about these things to her daughters Barbara and Marilyn. But, the stories either didnít filter down or, more likely, when people tried to tell me about these things, I simply didnít listen. Growing up, I did know two things: 1) Nova Rodomsk played some role in our family history; and 2) my grandmother was born in Czestochowa (I always heard it pronounced Czenstochowa but Iíll assume I simply heard it wrong). When I got older, my aunt published Toledot Littman1 which provided me with my first real understanding of the family history. But, even this book did not tell me much about my grandmotherís life in Poland. I had to find out for myself.

Source: Andrzej Zembik & Jacek Swaton, Czestochowa,

Na Starej Fotografii, 1994

Czestochowa Marketplace at the Turn of the Century - 50 Yards

from the Family Home

In May and June of 1997, my wife Susan and I had the chance to travel to Poland and get a glimpse into the life of our ancestors. I expected to find nothing. Itís been almost seventy-five years since the last of our ancestors left Poland. World War II had devastated the areas in which the Littmans and their descendants lived. Why would I expect to find anything? I was pleasantly surprised.

Where In The World Is Nova Rodomsk?

According to Toledot Littman, Schmuel Zanvil Littman and his son, Meyer Jonah Littman, lived in a town called Nova Rodomsk, Poland. The town has since changed its name to Rodomsko and is located to the south of Warsaw and just north of Czestochowa. It is here that I began my search for our roots.

Rodomosko can be easily reached by train from Czestochowa. The trains run approximately once per hour and cost 3.20 Polish Zloty (about $1.00). Iíll admit, it wasnít a first class train ride. But, then again, Rodomsko isnít a first class town. Itís a small, bleak town without much of anything. But, Susan and I went there armed solely with the map of the town contained in Toledot Littman.

The first thing we found was that the map we had brought was completely useless. I guess thatís to be expected when you attempt to use a 75 year old map which had been copied from a Yizkor book as your street map. First of all, the map is 90% in Yiddish which makes it impossible for anyone living there today to make heads or tails of it. Second, the town and its road system has grown and changed significantly in the intervening years. Third, even the street names shown in Polish have changed over the years. However, there were a few landmarks which helped to guide us. The major roads shown on the map still existed (under different names) and the plaza in the middle of town, shown on the map as 3-go Maja Plac2, still exists. However, standing in front of a small train station in a town where nobody speaks English, itís hard to get your bearings.

Fortunately, Rodomsko has two big signs, one in the center of town and one about a block from the train station, that show a current map of the complete town. I was able to line up the old map that we had brought with the one on the sign and was surprised to find that the map on the sign showed a cemetery exactly where the 75 year old map showed the old Jewish cemetery. In fact, it was the only cemetery shown on the sign. The Christian cemetery shown on my 75 year old Yizkor Book map was not marked on this new map.

Street Map of Rodomsko

The sign showed the cemetery being located on a street named Przedborska. The old Yizkor Book map taken from Toledot Littman showed the street name as being Limanowskiego (plus an even older Yiddish name). We decided to take a chance and see if, by some miracle, the cemetery where Schmuel Zanvil was buried was still standing.

After a long walk (several miles), we came across a large brick wall on our right. There were two solid metal doors in the wall. There was no way to see over the wall or through the solid doors but I knew this must be the place. I tried one of the doors and it opened easily. I couldnít believe what I saw. Inside was an enormous Jewish cemetery. Almost 90% of the stones were still standing and virtually all of them were readable (assuming you can read Yiddish). Susan and I began walking among the stones looking for the Littman name.

Almost immediately, a "caretaker" came out to see what I was doing. I put the word "caretaker" in quotes because I donít believe his job is to take care of the cemetery. Rather, I believe his job is to make sure nobody does it any harm. His home is within the cemetery walls and he spoke only Polish. Once I was able to convince him that I simply wanted to look, he went back into his house and left us alone.

The cemetery was completely overgrown. Judging from the dates on the stones, it was in use until 1986. There were well over 1000 gravestones in better condition than some of the cemeteries Iíve seen in New Jersey. In addition to the picture shown here, three pictures of the cemetery are shown in the book Jewish Cemeteries in Poland. The cemetery seemed to be laid out in a strange manner. Some sections contained only women while others contained a mixture of men and women. New stones seemed to be mixed with old. However, the stones from Schmuel Zanvilís time period appeared to be in the back left corner. Although Susan and I searched for several hours, we were unable to find his gravestone. But, Iím sure itís there. However, it would probably take several weeks to find it. Susan and I said Kaddish for him anyway (we didnít have a minyan, but we thought we should say it anyway).

Jewish Cemetery in Rodomsko

For anyone trying to find this cemetery in the future, it is located across the street from Przedborska 163. Przedborska has changed names several times over the years and some of the signs still contain the older names. As I said earlier, the street was named Limanowskiego until the communists took control of the area. Only one sign on the street (at number 88) still contains that name. When the communists took power, they renamed it Swierczewskiego. About 30% of the houses still have that street name on them. When the communists lost control of Poland, the name changed to its current name of Przedborska which is how it is shown on modern maps. Outside the cemetery there is a sign containing two daggers and a burning cauldron. (Note: The same symbol is shown on a sign at Auschwitz. It is an old Polish symbol for a cemetery for those who took part in some type of struggle.) The cemetery is a very long walk from the train station so I highly recommend a taxi. But, if you choose to walk (which we did given that we didnít know where to tell the taxi to take us), Przedborska starts at 3-go Maja Plac. Simply keep walking until you see the sign with the daggers and cauldron on your right. Plan to walk for over an hour.

On To Czestochowa

Schmuel Zanvilís son Meyer Jonah Littman lived in Czestochowa. It is here he had a daughter, Esther. Esther married Chaim (Hyman) Bratt. Esther and Hyman were Sylvia Zuckermanís, Florence Brodskyís and Anne Goldmanís parents. According to Toledot Littman, they lived in a small two story home with a courtyard in Czestochowa. I learned from Marilyn Brenner that the address was Krakowska 4. I also learned Harry Bratt, Chaimís brother, lived on Garncarska.

Once again, Susan and I set out to find these places using a map

weíd copied from Toledot Littman. This time, the map was more useful. As

it turned out Krakowska was less than 300 yards from our hotel. Garncarska

was only a few blocks farther. But, after all of these years, would anything

still be standing?

As we turned onto Krakowska, I was expecting another long walk. But, number 4, the number for Esther and Chaimís house, was the second one on the street. As soon as I saw the house, I knew it was the original building that the family had lived in. It had the courtyard and the metal gate just as Toledot Littman had said. The area where the outhouses had been now contained a small restaurant. But it was still standing, untouched by the years. Although we didnít know exactly which apartment theyíd lived in, we ventured inside for a closer look (where I proceeded to fall down the stairs smashing my video camera). There wasnít much to see inside but I could now say I had been there, walking in the same hallway where my grandmother had walked; fixing my video camera in the same courtyard where she had once played. This the home where Sylvia learned to bake. This is where Sylvia, Florence, and Anne learned to speak Yiddish. This is the courtyard where Anne would walk her pet chicken.

The House at 4 Krakowska in Czestochowa

I was surprised at how close to the main street they had lived. The main street in town, Najswietszej Marii Panny (NMP), is less than 50 feet from their home. I was also surprised by how close they lived to a church. There are two main churches in Czestochowa, one at each end of NMP. The smaller (and less famous) of the two is at the end of NMP within sight of their home. Although this part of town was the Jewish area, it also had a large non-Jewish population. In Toledot Littman, Florence had said she remembered hearing the church bells ringing every hour.

We then set off to find Garncarska. This street extended southerly much farther than shown on the map in Toledot Littman. Many of the buildings on the street have gone into complete disrepair over the years. Others have been rebuilt. But, on the whole, the street looks pretty similar today to how it must have looked when the Harry Bratt lived there. We didnít have a specific address for Harry Bratt so I canít say for sure if his home still stands.

Ul. Garncarska

Both Esther & Chaimís house and Harry Brattís house were relatively close to where the synagogue once stood. I was able to find a picture of the synagogue in a book entitled Czestochowa which contains pictures of the town early in the 1900ís. When I asked where the synagogue was, I was told to go to the Philharmonic building. It seems the Philharmonic building at Wilsona 16 stands on the site where the synagogue once stood.

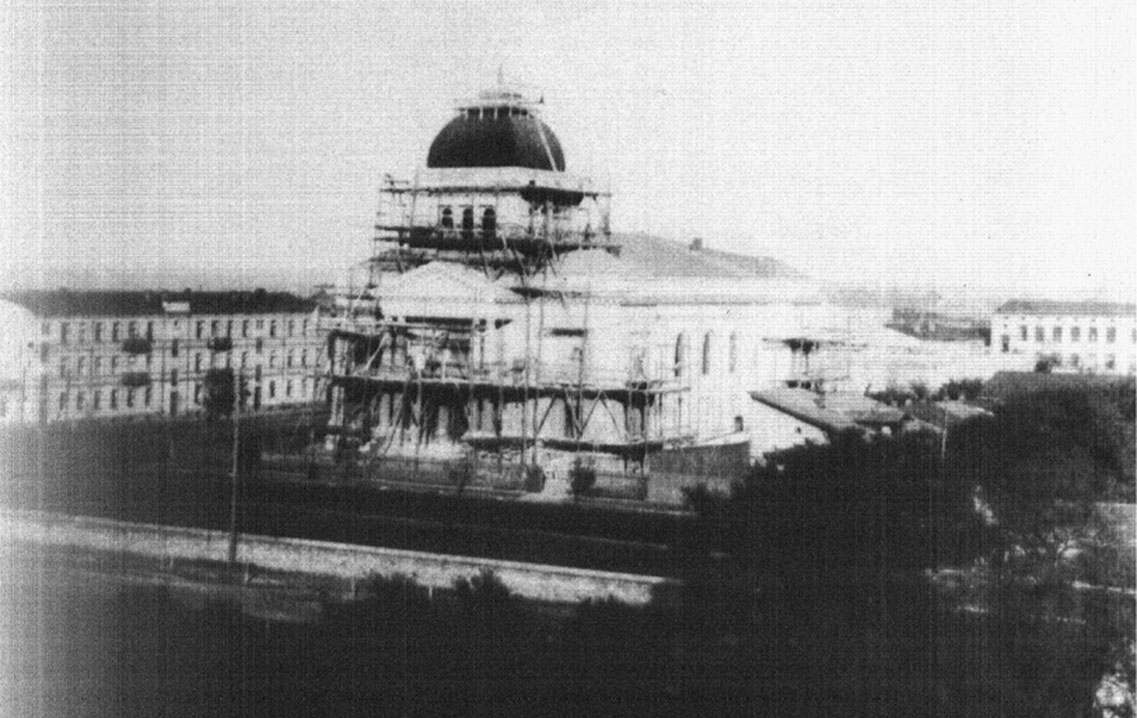

Source: Andrzej Zembik & Jacek Swaton, Czestochowa,

Na Starej Fotografii, 1994

Czestochowa Synagogue

The synagogue was destroyed by the Nazis and was never rebuilt. However, a plaque on the side of the Philharmonic building marks the location. The plaque is in Polish, Hebrew, and English.

Plaque at the Site of the Old

Czestochowa Synagogue

Coming Home

Iím sure I was the first Littman descendent to see the old family home in Czestochowa and the cemetery in Rodomsko in close to 75 years. It was exhilarating to be there and walk where our ancestors walked and see the things they must have seen. Iím glad to be able to show the rest of the family the pictures we took and share the experience.

On May 30, 1997, Susan and I sat in a small cafe in Czestochowa not

far from my grandmotherís home and ate a piece of chocolate cake3

while talking about her life. Iím sure grandma was there with us.

Footnotes: